While I sat in Hiroaki Umeda’s Split Flow, the various digital beeps and panes of light made me think of the many faces of Black people in America. As a survival mechanism, we are often trained to only show what is acceptable to the abiding power structures. In one situation, we cannot appear too intelligent, lest we risk sabotage. In another, we cannot be too reserved, lest we appear unqualified.

I wanted to document this quandary using the example of a Black dude who has usually followed white America’s rules, but is now ready to break out.

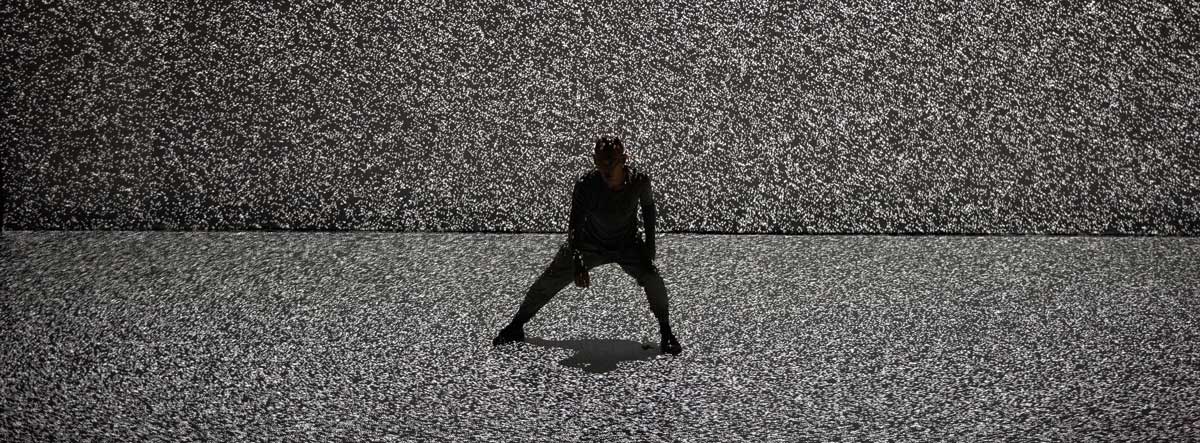

In response to Split Flow & Holistic Strata by Hiroaki Umeda

Behn had finally found his flow. His disparate, warring selves fell together like brothers at the end of fighting. Gazing into the mirror, he turned from ear to ear.

“You like ‘em? I told you the black would be nice.”

The tiny gems speckled in the afternoon light. In the corner of the piercing pagoda, an aging Indian woman waited with her child. Her eyes met Behn’s in the mirror. The corners of her red mouth turned courteously upward and then faded, as she turned to the sleepy Georgia street.

“So, you’ll keep ‘em in for six weeks. Rotate each piercing twice a day. Clean with this.”

He looked from the little purple bottle that she held out before him, to her hopeful face. Chamomile eyes. Baby-blue eyeshadow. Thin-plucked brows. Duck-bill bangs. Brown roots, blonde ends. Shimmering hot pink lips. Patient smile. He took the bottle into his hands.

“You okay, buddy?”

She patted his shoulders. Two gold rings sunk into her left hand. Metallic pink paint glinted from her fingernails in the gentle light. She was his guide, having brought him through the valley of indecision. If no one else was here, would you still want them pierced? And in doing so, she had stilled the voices, turned his mind’s eye away from shaking heads. This woman, whose name he did not yet know, was the great joiner, having brought his selves together. This thick-hipped hero was the great uncoverer, having brought to the surface Behn’s self within the self.

“I just need a minute.”

She smiled knowingly and took the Indian woman and her child to a chair on the other side of the pagoda.

Behn looked upon himself once more. Himself—née selves. There was a peace. But that peace had not been borne without struggle. He watched. Waited, for some sign of frothing rebellion just beneath the surface. Perhaps, his ears would swell. He tarried, believing that the fused selves might fissure once more. For Behn had been the many faces of the Negro. He could think of at least two—but perhaps he should call himself Legion; it was unclear how many voices, personas, loyalties inhabited the singular brown body. The first self, had been that of the Good Negro. The one who pressed his trousers, and tip! tip! tipped around in polished penny loafers. The Negro too busy to harm. This self was whiter than whiteness itself. He had studied the virtues, hoped to show himself approved. Yet it could not be so! Has it ever been so? But the Good Negro existed in loneliness. For too many negroes warranted white suspicion, charged the atmosphere with black power! even when they themselves tried to keep it under. So, the Good Negro was busy and short-haired and alone. In Knoxville, he set to the reading of Ethan Frome, chastened by Wharton’s stark New England scene. This is what happens when desire runs free. Perhaps, Wharton knew that beneath the crotch of his well-creased slacks, were tight testicles.

Behn turned his head to the other black stud and saw another self; the vision of the Artist. The suffocating Artist. Behn had refused to give this self air. Yet he fought, somehow surviving on scraps of inspiration. The Artist wanted to paint, wanted every surface to have texture and sound and color. But then the Artist could suddenly move towards a muted vision, seeing the minimal as an expression of utmost beauty. Behn could not subject himself to such vicissitudes, such shifting rainbow sands that threatened to interrupt his instilled collegiate order. The white supremacy under which the Good Negro operated was shit—but it was better than not knowing what to expect.

And now these strivings had ceased.

The Indian woman was now cooing, rubbing her hand through the child’s bowl of black hair. There were no tears on the child’s cheeks, ears newly adorned with little gold studs. The child smiled, seeing Behn gazing.

“I’m ready.” His eyes still on the bright child. “I’m ready to pay.”